Soft magnets — ferromagnetic materials that can easily switch their magnetization under the force of a weak magnetic field — play an important role in modern electronic equipment and electrical devices. They are used in smartphones, PCs, laptop chargers, electric generators and vehicles, wind turbines, MRI machines, and many more applications, essentially, anywhere magnetic fields need to be switched in alternating directions repeatedly. Causing the magnetic dipoles in such materials — the current at each atom in the crystalline lattice — to switch between two opposite directions — is what converts energy, whether magnetic or electrical, into work.

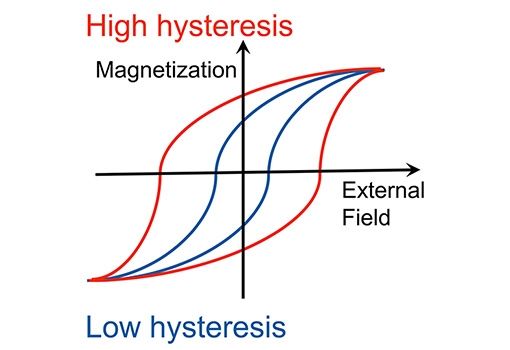

This switching cycle occurs up to millions of times per second, but not instantaneously; rather, there is a very brief lag between when an applied field initiates the cycle and when the dipoles switch. The lag phenomenon is called hysteresis, and over time, it adds up as a source of inefficiency that represents the energy lost across millions of cycles. A graphical plot of the phenomenon resembles a loop. In soft magnets, the loop tends to be narrow, indicating that little energy is required to change its magnetic state. For soft magnets, the narrower the loop, the more efficient the magnetic switching is and the less energy is lost in the process, typically as heat, which, in turn, requires more energy to be used for cooling.

Hongyi Guan, a third-year PhD student in the lab of UC Santa Barbara materials assistant professor Ananya Renuka Balakrisha, has taken a novel approach in developing a new model to simulate and understand the hysteresis loop. His findings are described in an article titled “Hysteresis and energy barriers in soft magnets,” and was published in the April 11 issue of the journal Physical Review Materials.

“Over time and across millions of cycles, even small losses add up,” Guan says.

“Shrinking the hysteresis loop means improving energy efficiency, and our research offers a new perspective that can be useful in exploring new soft-magnet materials.”

“The way we think of it, schematically, is that every lattice site, occupied by an atom, has a certain inherent spontaneous net magnetization, or magnetic dipole, associated with it,” Renuka Balakrisha explains. “The orientation of this dipole — the magnetic spin — causes the lattices to elongate a very small amount, between about 0.0001 percent and 0.1 percent. The lattice cells stretch and squeeze individually in response to the external magnetic field, and when all of them do it collectively, they can generate significant stresses that affect the rotation, or reversal, of the magnetization.

“Previously, in working to shrink hysteresis loops in soft magnets, researchers largely ignored these small forces, focusing instead exclusively on the magnetic properties of a given material,” she adds. “Hongyi has modeled a way to consider the dynamics of stretching and contracting in specific magnitudes to reduce the barrier for switching.”

“Showing that a carefully tuned combination of mechanical stress and magnetic behavior can dramatically shrink hysteresis loops,” Guan says, “opens up new possibilities for designing next-generation magnetic materials that are both high-performing and energy-efficient.”

Noting that Guan has collaborated on this project with UCSB mathematics professor Carlos Garcia Cervera, Renuka Balakrisha says, “One thing I really like, which I think Hongyi also appreciates, is that he can talk to both of us. He can talk with me about what I know about magnets, and can discuss the math with Professor Garcia Cervera, who is well known in the micromagnetics community and has been developing algorithms to solve these models for a very long time.”

One challenge for models of multi-physics systems is a lack of adequate computing power to solve them. Guan’s model avoids this in a clever way. Rather than solving equations for an intractable number of variables across the entire system, which would require years of computation on supercomputers, he resolves the model only for small, representative regions to predict the behavior of the material as a whole. “

Using his micromagnetics framework, he can decompose the magnetic object into a tiny representative volume and resolve those domains at nanometer scales, while still taking into account the shape of the macroscopic large object of which they are part,” Renuka Balakrisha says. “That gives him accurate values that he can validate against experiments. He has really accelerated how we can map the effect of these tiny domains on magnetic macroscopic properties, one of which is hysteresis.”

Guan pioneers new terrain by modeling how to combine the magnetic switching and the inherent stresses to enhance efficiency in a soft magnet. “The way materials scientists generally approach making magnets, whether an alloy or a thin film of magnetic material, is to tune a single material constant that makes the hysteresis very small,” Renuka Balakrisha explains. “But in his work, Hongyi has explored additional dimensions in the parameter space, considering not only material parameters related to mechanical coupling but also another important element — the anisotropy constant — which is related to the fact that each time a dipole is rotated to a new direction, the system incurs a kind of penalty in the form of energy required to overcome the material’s resistance to the change.

“The material will tell you, ‘No, I'm comfortable here; stop doing this,’” Renuka Balakrisha continues. “So, it requires extra energy input. A lot of metallurgist experimentalists have looked at minimizing that penalty when they mixed different elements together to make a soft magnet. But Hongyi can show that, even if you have a magnet that incurs a huge penalty to rotate, if you design your lattice distortions in a clever-enough way, that combination of the two — the right material and the right engineering of those stresses — can result in a magnet with small hysteresis.”

“It takes a long time to make a specific material, and it is unlikely that a new soft magnet identified experimentally will be cheap enough and sophisticated enough to be scaled up for manufacture,” Guan notes. “The advantage of the computational approach is that the model can increase the scope of possible new materials by identifying many promising combinations that meet specific criteria. Our model could, therefore, accelerate the discovery of new soft magnets.”

“In the bigger picture,” Renuka Balakrisha adds, “this allows material scientists to look for composition spaces that were not explored previously, because these material constants were not intuitively thought to have small hysteresis. Hongyi’s software can guide researchers who are looking for new combinations of elements on the periodic table.”

A graph depicting hysteresis loops in magnets. The narrow blue loop shows a material that switches its magnetization with minimal energy loss, while the wider red loop represents a material that requires stronger fields and loses more energy during switching.